Back in the early 90s, my older brother managed to get me a second-hand Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). It came with two games which, as I had no money to buy any others, occupied much of my time for months on end. One was the classic arcade game Kung Fu Master and the other was Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

Whilst Kung Fu Master didn’t take long to, er, master, TMNT was a different beast. It was impossibly difficult. It was so difficult that, along with a handful of other NES games, it contributed to the phrase ‘Nintendo hard’ entering the English language. Some of the levels were almost unplayable (I seriously think the one with the van was solely created just to crush the spirit of children), but what made the whole experience impossible was the fact that this was in an era when there was no ‘save game’ feature on consoles. So every time I lost the game, I had to start again at the beginning. I don’t want to work out the number of hours I threw away making barely perceptible progress on TMNT.

But as the saying goes, ‘When I became a man, I put away childish things’. Whilst anyone who even vaguely knows me would know that this obviously isn’t even slightly true of me, I have definitely moved on from wasting endless hours trying to overcome such frivolously difficult tasks – tasks where I ultimately get nowhere and have to start right back at the beginning again after each attempt. That is until I became an English teacher. Because, since I became an English teacher, I’ve had to take part in standardisation. Regularly.

Standardisation, to the uninitiated, is the act of moderating assessment with colleagues in order to establish a standardised level of accuracy in grading. Seems like a wholly appropriate thing for any English department to do, particularly in the days of coursework and controlled assessment. The problem is that standardisation, whilst well-intentioned and seemingly necessary, is a bit like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles on the NES.

Because moderating and standardising assessment, certainly in English, doesn’t mean we get standardised grades. Like TMNT, we seem to make progress whilst we are standardising: agreeing on grades and reaching some kind of harmony with our marking. But also like TMNT, the next time we come back to the marking, we have to start all over again: much of what we gained in the standardisation process is lost.

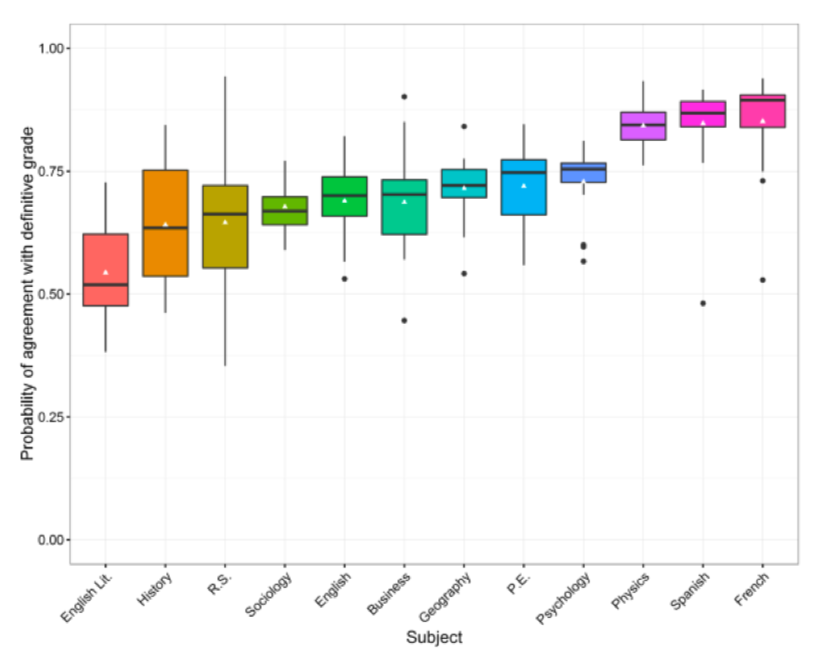

If you don’t believe me, take a look at the Ofqual report, ‘Marking consistency metrics’, on the quality of marking in general qualifications. Bear in mind that examiners of GCSEs and A Levels undertake more rigorous standardisation than your regular classroom teacher, the findings of the report are pretty depressing. For their report, Ofqual put seeded papers (those that have been pre-marked and assigned definitive marks) out to be remarked by the team of employed examiners. Below is a table showing the probability of a candidate being award the definitive mark. For English Literature, it’s around 50%. History isn’t much better at around the 60% mark.

The elephant (or turtle) in the room when we standardise is that, when left to our own devices, much of what we gained in standardisation is lost – lost to unconscious bias, lost to the subjective nature of grade descriptors, lost to tiredness, lost to caprice, lost to the fact we might subconsciously compare against the previous piece of work we marked.

And yet we still seem to give up lots of time to standardisation.

The idea that, by practising assessing, and by moderating with colleagues, we are standardising our marking and getting more accurate is a tantalising one. And tantalising is the perfect word for the whole process, as its very etymology brings to mind another good analogy for the largely futile activity. For the word derives from the character in Greek myth, Tantalus, who was punished by his father, Zeus, in a rather spectacular way. Tantalus, a mortal, was invited to dine with the Gods on Mount Olympus. He wanted to test whether the Gods really did know everything, so (obviously) he decided to kill his own son, Pelops, chop him up, cook him and serve him up to see if they knew what they were eating. The Olympians immediately knew what had happened (except Demeter, who was probably looking at her phone and so wasn’t paying full attention). Zeus then dished out the most delicious punishment: Tantalus was made to spend eternity in a pool of water which sat beneath trees hanging with bounteous fruits just above his head. But every time he bent to drink the water, it would drain away so he couldn’t get to it, and every time he tried to reach the fruits above his head, they would rise up away from his grasp. Hence: tantalising – ‘tormenting or teasing with the sight or promise of something unobtainable’.

That’s the perfect analogy for standardisation: it torments and teases us with a promise of accuracy, something that is ultimately unobtainable. We should probably be cautious about investing too much time on it. Which is exactly what my mum kept telling me about Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Mums are always right.

(Yes, gamers, I know it was called ‘Teenage Mutant *Hero* Turtles in the UK; the original US title is used here to avoid quizzical responses from non-European readers.)