The way that artists have portrayed education throughout history has been something of a fascination for me in recent years. Over a series of blog posts, I have explored how artists from various eras and artistic movements have cast their eyes, their brushes, their lenses and their, er, casts over the educational landscape before them. You can catch up with these blog posts by clicking on the links below.

An art history of school inspections

An art history of back to school

In today’s post, I will be looking at the various artistic representations of the longest and darkest period of the academic year: the autumn term.

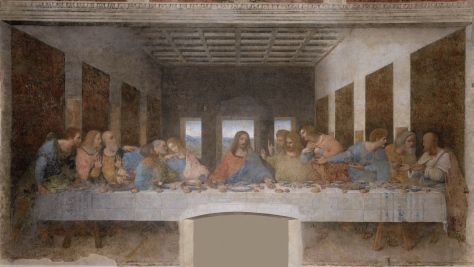

I’ll be begin by discussing one of the most famous paintings depicting the beginning of the autumn term: Leonardo da Vinci’s celebrated ‘The First Seating Plan’ (1495-8).

In this painting, we can see the teacher surrounded by his pupils as they react to the seating plan that the teacher has placed them in. As da Vinci leads our eyes across the painting, we can see many students arguing that they don’t want to sit next to their designated partner, while others are still trying to work out where they actually sit from the simple diagram projected onto the whiteboard. But most striking is the teacher’s expression, which we can see in the detail below. His face simply says, “If getting them to sit in a seat is this hard, how on Earth am I going to teach them quadratic equations?”

French painter Jean-Antoine Watteau also worked on this theme of the first seating plan in his 1718 work, ‘Get in! We’re sat together!’ (below), which focuses on the moment that a group of pupils show enthusiasm for the teacher’s random seating plan by hugging and dancing with each other. Of course, the moment that pupils show excitement at such serendipity is also the moment that the teacher’s heart sinks and they realise that they’ve really cocked up the seating plan by placing these pupils where they are obviously going to easily distract one another. She’ll give them a chance, but she’s pretty sure that the seating plan will have to be redone tomorrow.

One of my favourite physical pieces of autumn term art is Tony Cragg’s sculpture, ‘All of the water bottles you’ve lost this term’ (1998).

In this piece, you can see the sheer volume of water bottles that a single teacher has brought into school during the autumn term, only to leave them somewhere and never get them back. You’ll notice plenty of common plastic mineral water bottles, as well as a number of flasks and fancy designer receptacles, including the expensive one that the teacher bought at the end of the summer holidays as a gift to themselves for the new term. They lost that one during inset on the first day back. The artist said of this piece, “If you think that the oceans are full of unwanted and left-behind plastic bottles, you should see school staffrooms.”

Whilst Cragg deals with the subject of drink, many artists turn their attention to teachers’ food during the autumn term. It is often striking in schools how little time it takes for cake to become a common sight in the staffroom, as teachers begin to ramp up their sugar intake in order to survive the autumn term. Below we can see Chris Killip’s 1977 photograph, ‘Teachers queuing outside the cake shop, two weeks into term’.

Killip’s piece is an important piece of photojournalism, capturing the sugary reality of this first term.

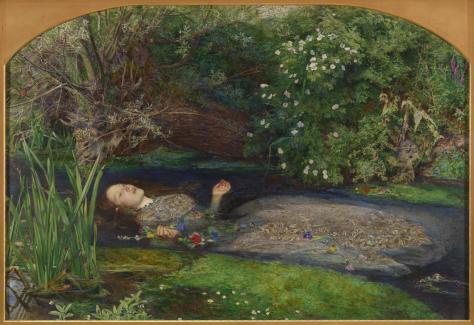

But whilst cake becomes a common in the mise en scène of the staffroom, there’s alway someone who, with good intentions, brings fruit in for colleagues. This has, of course, famously been portrayed by Sir John Everett Millais in his 1849 painting, ‘Fruit? Are you ****ing joking mate?’, as seen below.

Critics have heaped praised on this painting, as it captures the well-meaning teacher bring a bowl of oranges into the staffroom, only to enrage her colleague, who was expecting, at the very least, a family pack of Kit Kats to see him and his colleagues through the morning.

As the term progresses, teachers often face their heaviest marking load of the year, as baseline assessments and data drops build up and mock exam period is swiftly upon them. This creates a seemingly endless pile of marking.

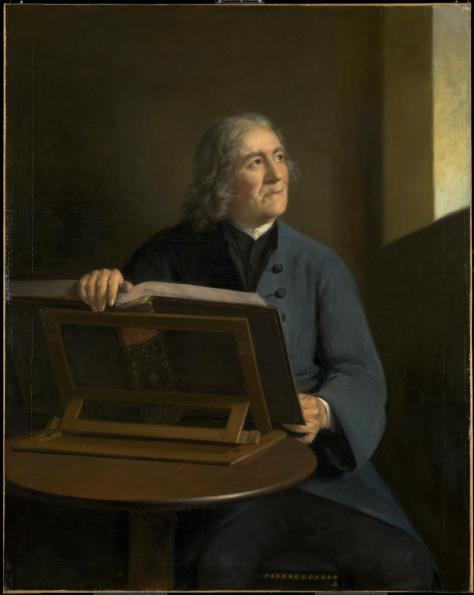

Thomas Gainsborough’s late 18th century work, ‘When will this mock exam marking end?’ expertly captures the mood of teachers at this time. Note the heavy reams of paper, as well as the wistful look on the teacher’s face has he remembers the days when he could spend time with his family. Viewers are drawn to the small square of light in the top right hand corner, symbolising the fragments of hope that keep teachers going throughout this time.

On the subject of light, J.M.W. Turner’s masterpiece of chiaroscuro (below) addresses the dominating feature of the autumn term: its perpetual darkness.

‘Hello Darkness, My Old Friend’ (1890) depicts a teacher planning their lessons and marking books as the ubiquitous darkness of autumn term creeps in all around them. The lack of light plays heavy on the teacher’s mental state as their hand quivers near their face. Turner deliberately leaves any indicators of time out of the painting, suggesting that this could be 8 o’clock in the morning, 4pm, or midnight. Let’s face it, they were probably sat there at all three times.

As the term goes on, the darkness and workload take their toll on a teacher’s energy. You will all recognise Millais’ famous painting depicting this subject below.

During the latter part of the term, teachers find they no longer have the energy to stand in the shower at the end of the day. In ‘Bath, not shower’ (1851-2), Millais shows us the teacher reverting to lying in a bath out of necessity, complete with Lush bath bomb, a weary look, and – in this extreme case – all her clothes on. It’s fine though – all her colleagues will be so tired that they won’t notice that she’s wearing the same dress for two days running, this time with added creases and still dripping dry. “You smell nice,” they might say.

Late in the term, the weather begins to turn and we get our first cold snap. Tired and in need of any extra time they can get to catch up with marking or sleep, teachers often see the possibility of a glimpse of respite in this cold weather.

‘Praying for Snow’ (1888) by Alphonse Legros

‘Praying for Snow’ (1888) by Alphonse Legros

Alphonse Legros’ ‘Praying for Snow’ (1888) shows the moment when teachers desperately wish for a day to catch up contemplate the educational opportunities a day of snow will bring to the children they teach.

As Christmas approaches, there is an air of excitement in the school. Departments will often celebrate the season by organising a Secret Santa gift-giving amongst themselves. David Hockney’s painting below depicts the moment of the exchanging of gifts.

In ‘Oh good – a book about teaching’, the artist shows us the faux gratitude shown by the teacher (on the right) receiving the gift, as he receives a book that is guaranteed to mean that he has to think about work throughout the Christmas holidays too. The teacher on the left seems satisfied that she bought him this instead of the Borat-style mankini she originally thought about getting him. Clearly, he would have preferred the mankini.

The final week of lessons approach and teachers and pupils alike can see the end in sight.

In the above painting, Richard Redgrave’s ‘Can we have a fun lesson?’ (1851), we can see the teacher responding angrily to the question that he has been asked 14 times already this week. There are still two days to go.

On the final day of term, the question becomes even more deploring. Frederic George Stephens’ ‘Can we watch a DVD?’ shows a pupil begging to be allowed to watch the first half of a film before going to their next lesson to ask their next teacher if they can watch the first half of a completely different film, and so on for the rest of the day. It is arguable that such a day would actually have an educational benefit: it will serve as a good introduction to postmodernism and will ably prepare pupils to read James Joyce or Italo Calvino in the future. In Stephens’ painting, we can see the teacher wrestling over the decision to teach her planned lesson, watch an educational documentary or just give in completely and stick Elf on.

Once term is finished, teachers can really get into the seasonal festivities with their friends and family. Tom Hunter’s ‘Get the Party Started’ (2009) shows a teacher, back home after the long autumn term, really throwing themselves into all of the festive fun and cheer.

That’s it for this look at the art of the autumn term throughout history. I hope you’ve enjoyed it. See you next time!