This is the third in a series of blogs on the key philosophers of education. Part 1 can be found here. Click here for Part 2.

A.S. Neill

Neill was a Scottish educator who is most known as the founder of Summerisle, a school that gained notoriety in the 20th century for its progressive philosophy. He was famously portrayed by the actor Christopher Lee in a 1973 film about life at Summerisle.

Neill was a very poor student at school, so he decided to become a teacher. It turned out that he was also a very poor teacher, so he went into school leadership instead.

Neill co-founded a progressive school in Dresden in 1921. This school taught Eurhythmics, a new wave synth pop band, which is basically like people teaching Stormzy today.

Neill left Germany in 1924 and founded Summerisle in Dorset. He then moved the school from Dorset to its present site in Suffolk in 1927, a move that clearly influenced footballer Matt Holland some 70 years later, when he left AFC Bournemouth to sign for Ipswich Town in 1997 for £800,000. Unlike Holland, Neill remained in Dorset for the rest of life. Holland, of course, signed for Charlton Athletic six years later and became a club legend. Holland also represented the Republic of Ireland thanks to an Irish grandmother. As far as I am aware, A.S. Neill has no international caps for a country that he has only a tenuous connection to.

In his biography of Neill, Richard Bailey describes an algebra lesson taught at Summerisle by Neill himself, saying that his “explanation of algebra was incoherent” and concluding that the lesson was “simply awful”. Neill was clearly ahead of his time though as the same lesson would almost certainly have been graded ‘outstanding’ in the 2000s.

Bailey also says of that same lesson that Neill “dealt with individual difficulties by resorting to insults”, thus revealing the provenance of the approach taken by other high profile progressive educationalists on social media today.

Socialist author Ethel Mannin wrote of Summerisle in 1930 that it “is, I think, the happiest place in the world”. But then, at the point, she’d never been to a TGI Fridays.

R.S. Peters

Richard Stanley Peters was the protagonist in the BBC sitcom Porridge, who later went on to do philosophy and that.

R.S. Peters famously created the concept of ‘the educated person’. Before Peters, all people were idiots.

Peters’ defined ‘the educated person’ as someone who is in pursuit of truth, a bit like Anneka Rice in Treasure Hunt. Peters doesn’t specify whether the educated person needs to wear a tight-fitting jumpsuit, so that’s probably optional. I just wear one to be on the safe side.

Other characteristics of the educated person are:

- can eat three Shredded Wheat

- knows all the dance moves to ‘Saturday Night’ by Whigfield

- can get at least to level 6 on Snake on a Nokia phone

- has watched all of The Matrix movies without getting bored

- doesn’t tweet about it when they get a question right whilst watching University Challenge

- can name all of the S Club Juniors

- can see magic eye pictures without showing off about it

- constantly questions why only the orange Smartie is flavoured and yet all of the other seven colours aren’t

- has no time for music these days – it all sounds the same

- hasn’t fallen for the big olive con of having multiple different types of olives to choose from when they all just taste like salt anyway

- can recite pie to 12 ingredients

In 1981, the Ford Capri RS Turbo was introduced to Europe. Contrary to the popular belief that the RS stands for ‘Rallye Sport’, it is actually named after R.S. Peters. Ford went on to produce RS versions of many of their cars, including the Escort, the Fiesta and the Sierra. A fitting tribute to a great philosopher, I’m sure you’ll agree.

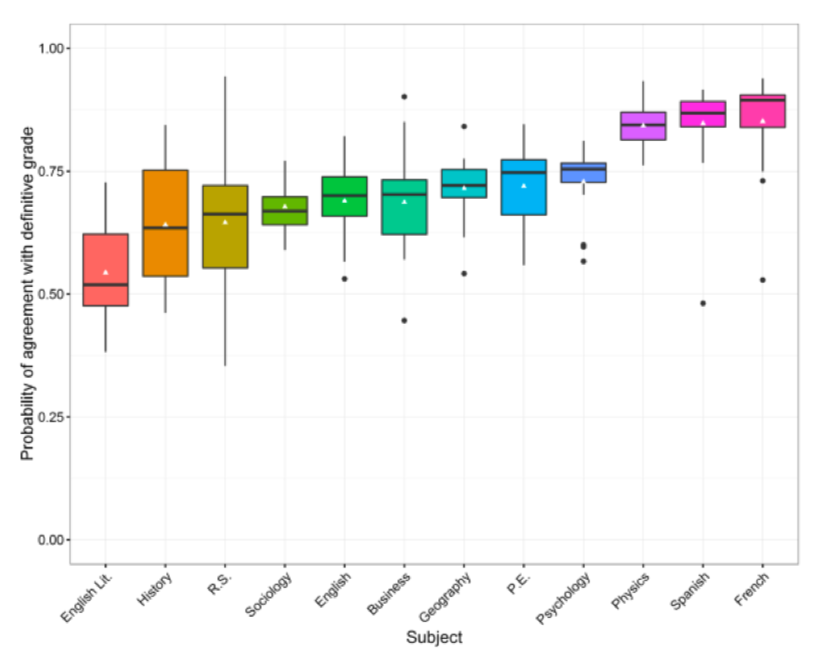

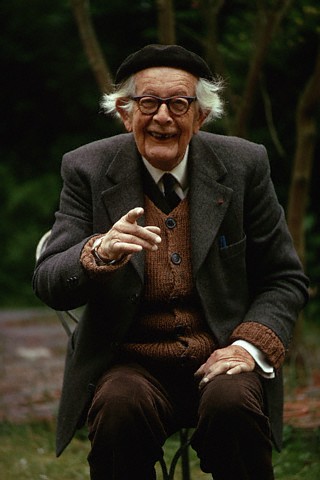

Jean Piaget

Jean Piaget was a Swiss psychologist whose work has heavily influenced Western philosophies of education. In a 2002 survey, he was ranked as the second most eminent psychologist of the 20th century, after Frasier Crane, but ahead of all of the Ghostbusters.

Piaget came up with a theory of cognitive development, which he cleverly called ‘Piaget’s theory of cognitive development’. Within this theory, Piaget identified four stages of cognitive development, which corresponded with different ages of our lives.

The first stage is between the ages of 0 and 2 years old, and is called the sensorimotor stage. Within this stage, children develop an understanding of object permanence: the idea that an object continues to exist even though you can’t see it, like when I left my lunch at home this morning and I know that it’s still on the side where I left it. This is not to be confused with when a pupil leaves their homework at home, which is called object fabrication.

During the second stage, called the pre-operational stage, children cannot understand concrete logic or mentally manipulate information. This occurs between the ages of 2 and 7 years old, but can be triggered again in adulthood by simply placing a MAGA cap on your head.

The third stage is the concrete operational stage and occurs between the ages of 7 and 11 years old. According to Piaget, this is the stage when the child can use logic appropriately. But if this is true, why do some children sometimes ask their teachers if they remember World War I or if Shakespeare is still alive? Also, I still don’t understand Inception and I’m 44 years old.

The final stage is the Aztec Zone, and after that you get to go to the Crystal Dome and collect gold and silver tokens. For every crystal you picked up over the four stages of cognitive development, you get five seconds in the Crystal Dome.

Piaget’s theories have been criticised for being “conceptually limited, empirically false, or philosophically and epistemologically untenable”. Piaget’s influence on education academia and research today is massive.

(Editor: Are these last two sentences meant to be separate points? Shall I put them into separate paragraphs before publishing? It just looks like you are making a link between those two points and I’m not sure that you meant to do that?)

(Editor: Hi, did you get my message about the last two points?)

(Editor: I’m not getting any replies, so I’ll just leave them as they are and hope you haven’t made a terrible mistake.)